Every year I hear the same worry from gardeners: “Why are my tomato leaves turning yellow?” It’s a fair question. Nothing sets off alarm bells like watching a once-vibrant plant start to lose its color.

I’ve grown tomatoes for years, and I can tell you yellowing leaves are one of the most common issues I troubleshoot in the garden. The important thing to understand is this, yellow leaves aren’t random.

They’re signals. My job as a gardener is to read those signals and respond before the plant’s health or harvest suffers.

Water Stress: Too Much or Too Little

One of the first things I check when I see yellow tomato leaves is water. Tomato plants are particular about moisture, too much, and the roots drown; too little, and the plant can’t pull in nutrients.

Overwatering often leads to yellowing from the bottom up, because the roots sit in soggy soil and lose access to oxygen. Underwatering, on the other hand, causes leaves to wilt, curl, and yellow as the plant diverts what little moisture it has to critical areas.

The tricky part is that both problems look similar at first glance. That’s why I always check the soil before assuming. I’ll push a finger a few inches down, if it’s dry, the plant is thirsty.

If it’s wet and heavy, I know I’ve gone too far with the watering can. Mulching around the base of the plant helps me regulate this balance, locking in moisture while preventing soil from staying too damp after a heavy rain.

The fix is about consistency. Tomatoes thrive on even moisture, not extremes. I aim for deep watering two to three times a week rather than shallow daily sprinkles.

With proper drainage and a steady rhythm, the yellowing leaves often stop in their tracks.

Nutrient Deficiencies

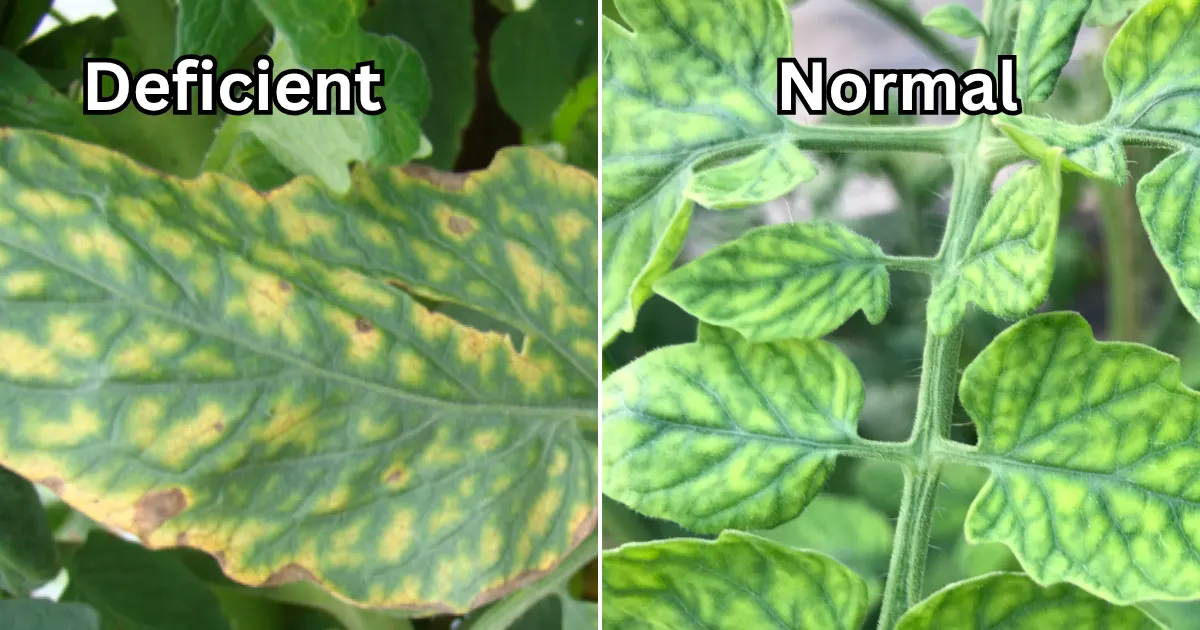

The next major cause I consider is nutrition. Tomatoes are heavy feeders, and when the soil isn’t meeting their demands, the leaves quickly show it. A nitrogen deficiency usually shows up as overall yellowing on older leaves, since nitrogen is mobile within the plant.

Magnesium deficiency creates yellowing between the veins, leaving the veins themselves green. Iron deficiency tends to strike young leaves first, turning them pale with dark green veins.

When I see these patterns, I don’t guess, I test. A basic soil test tells me exactly what’s missing. Once I know, I can target the deficiency instead of overloading the soil with a generic fertilizer. For nitrogen, I’ll use composted manure or a balanced fertilizer.

For magnesium, Epsom salts dissolved in water provide a quick fix. Iron deficiencies often indicate pH problems, but chelated iron sprays can provide relief in the short term.

Balanced feeding is key. Tomatoes don’t just need one nutrient; they need a steady supply of all the major and trace elements. I’ve learned that steady, moderate fertilization is better than a heavy dose all at once.

By addressing the specific deficiency, yellow leaves usually recover or new growth emerges healthy and strong.

Also Read: How to Treat and Prevent Corn Smut Disease

Soil Health and pH Imbalances

Even if I’m feeding my tomatoes well, poor soil health can block them from absorbing nutrients. Soil pH plays a huge role here. If the soil is too acidic or too alkaline, nutrients remain locked up and unavailable to the roots.

For tomatoes, I aim for a pH between 6.2 and 6.8. Outside that range, even well-fertilized soil can leave plants starving, and the leaves show it by turning yellow.

I make it a habit to test my soil pH every season. When it’s too acidic, I’ll add lime to raise it. When it’s too alkaline, elemental sulfur brings it back down.

These adjustments aren’t instant, they take time to work into the soil, so I plan ahead. Alongside pH balancing, I keep my soil rich with organic matter.

Compost, aged manure, and cover crops all improve soil structure, which supports healthy root growth and consistent nutrient uptake.

A healthy soil ecosystem doesn’t just correct deficiencies; it prevents them. By caring for the soil, I create an environment where tomatoes can thrive without constant crisis management.

Whenever yellowing leaves crop up, I remind myself to look beyond the plant and focus on what’s happening underground.

Pests and Diseases

Unfortunately, not all yellow leaves are the result of water or nutrients. Sometimes, the culprit is alive and actively attacking the plant.

Pests like aphids and spider mites suck sap from the leaves, leaving them speckled, yellow, and weak. Whiteflies create similar damage, often accompanied by sticky residue. These pests don’t just stress the plant, they open the door to diseases.

Fungal diseases are another frequent cause of yellowing. Early blight and septoria leaf spot are especially common in tomatoes. They start as small yellow spots, which expand and eventually turn brown or black.

The disease spreads upward from the bottom leaves, often thriving in warm, humid conditions. If left unchecked, they can defoliate a plant before fruiting even begins.

I deal with these issues by being proactive. Regular pruning improves airflow and keeps lower leaves from touching the soil, where many pathogens lurk. I rotate crops yearly to prevent disease buildup.

For pests, I rely on insecticidal soap or neem oil, always applied carefully so as not to harm pollinators. When fungal issues arise, copper-based fungicides and strict sanitation keep the problem under control. By catching these problems early, I can usually save the harvest.

Environmental Stress Factors

Sometimes yellow leaves have nothing to do with soil, water, or pests. The environment itself can stress tomato plants. Transplant shock, for instance, often causes yellowing after young plants are moved into the garden. The roots are adjusting, and the plant temporarily struggles to balance growth and nutrient uptake.

Temperature extremes also play a role. Prolonged cold nights or blazing hot days can cause stress that shows up as yellowing or stalled growth. Similarly, inadequate sunlight weakens the plant and reduces photosynthesis, leading to pale, yellow leaves.

In my experience, tomatoes need a full six to eight hours of direct sun daily to thrive.

The fix is often preventive. I harden off seedlings before transplanting so they adapt gradually to outdoor conditions. Shade cloth helps during heat waves, while row covers protect against unexpected cold snaps.

By managing these stress factors, I reduce the chances of yellowing leaves appearing in the first place.

Also Read: How to Prevent and Treat Cabbage Worm Infestation

Natural Aging and Pruning

Not every yellow leaf is a sign of trouble. As tomato plants mature, the oldest leaves naturally turn yellow and die off. This usually happens at the bottom of the plant, where the leaves have already served their purpose.

I’ve learned not to panic when I see a few older leaves yellowing as fruit production ramps up.

The key is knowing the difference between natural aging and a true problem. If the yellowing is limited to lower leaves and the rest of the plant looks strong, it’s usually just part of the life cycle.

On the other hand, if the yellowing spreads quickly or affects new growth, I know I need to investigate further.

I often prune these older yellow leaves to improve airflow and direct the plant’s energy toward producing flowers and fruit. This not only keeps the plant healthier but also makes it easier for me to spot problems early on. In a way, yellow leaves are part of a natural pruning process that helps the plant focus where it matters most.

FAQs

Yes, I remove them to improve airflow and reduce disease risk, but only after addressing the underlying cause. I water deeply two to three times a week, adjusting for weather, instead of shallow daily watering. Not at all. If I act quickly, the plant usually recovers and continues to produce a healthy crop. Should I remove all yellow leaves from my tomato plants?

How often should I water my tomatoes to prevent yellow leaves?

Are yellow leaves a sign my tomato plant won’t produce fruit?